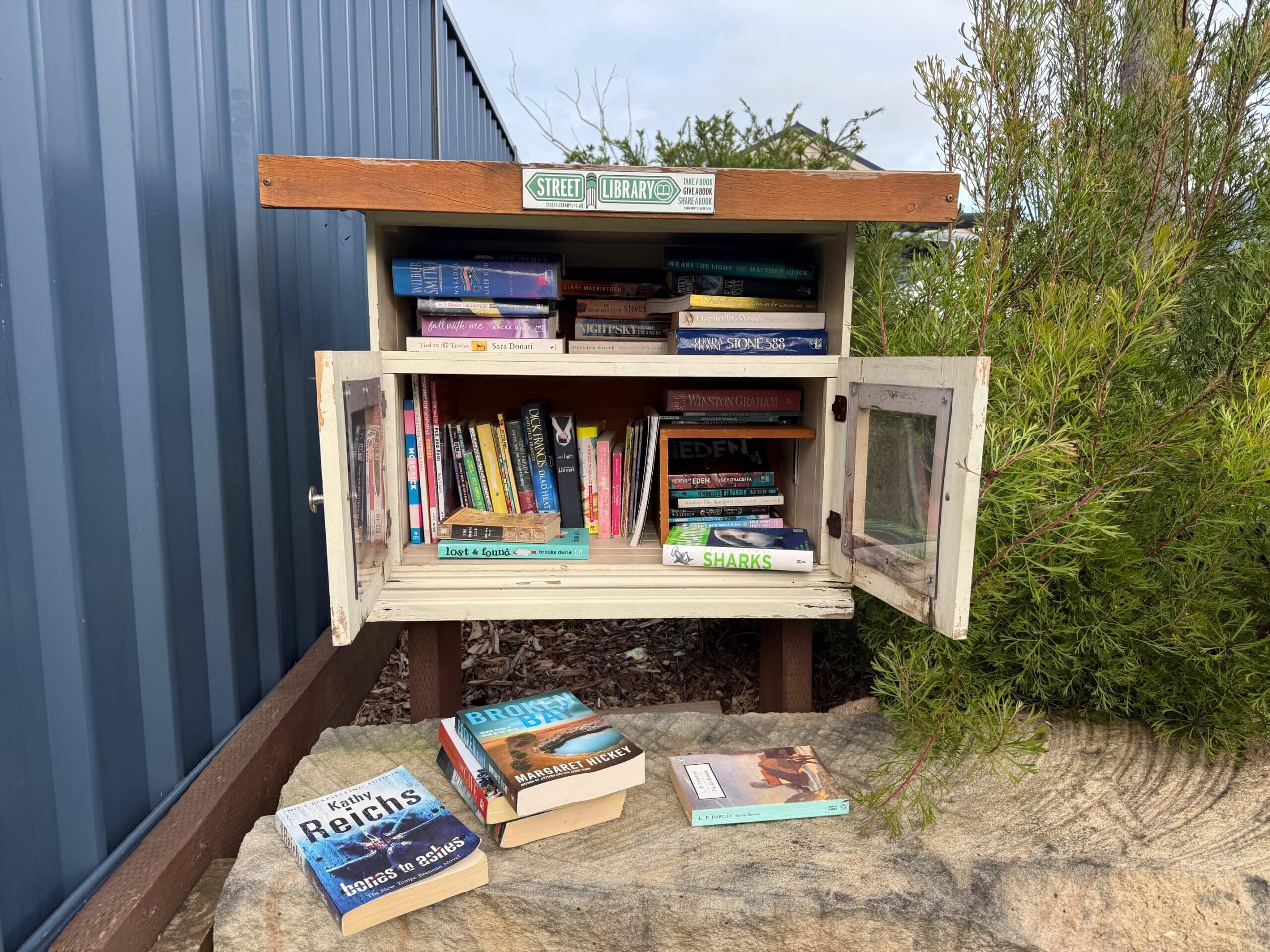

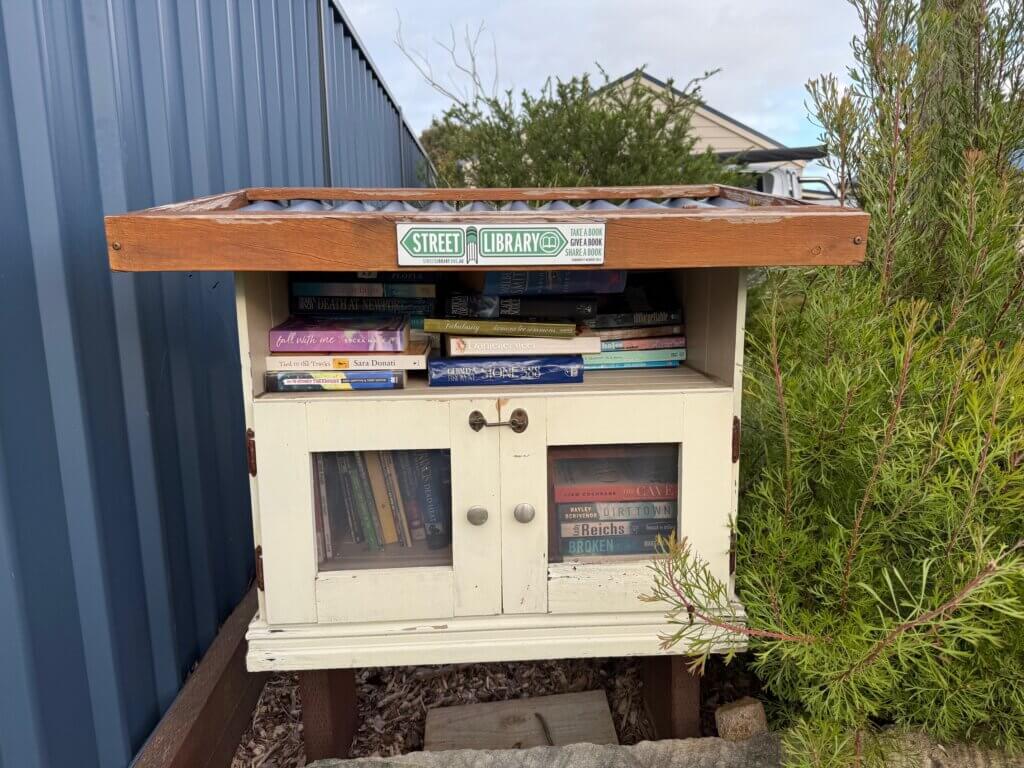

Figure 1: Street Library, Medowie, May 2025. Source: Gemma Lavings*

Medowie's Street Libraries: borrowing and sharing public space

One of the major themes of our project is that public spaces require care to be relevant and useful to their communities. Throughout our research, we have noticed that taking care of public space is also taking care of social life. In this guest post, Gemma Lavings, a Macquarie University Bachelor of Arts student, looks at how street libraries provide both opportunities and challenges to ordinary people in caring for public space. Gemma’s exploration of the rich range of street libraries in her hometown of Port Stephen’s suburb Medowie takes us on a tour of how streets and neighbourhoods are transformed by small, everyday acts of care that invite passersby to share books.

Street libraries

A steadily increasing phenomenon over the last five years, street libraries are small free-standing or semi-attached structures located in open and accessible spaces, such as parks, nature strips or fences outside houses. After being established by a street librarian, the small, weatherproof containers for books that street libraries represent contain books that anonymous individuals have left or swapped (Fig. 1). These ordinary, DIY activities of care for and within public space promote a public and continuous exchange of books at no monetary cost (Chen 2022: 27)--a purpose typified in the global movement's slogan ‘Take a book. Give a book. Share a book’.

As of 2025:

- there were nearly 6,000 registered street libraries in Australia

- around half of these were in New South Wales

- the City of Parramatta topped the nation with over 120 local street libraries!

As of May 2025, there were 8 of these street libraries in the suburb of Medowie, and the remainder of this story takes you on a tour of them...

Nurturing community bonds

Street libraries fundamentally require a sharing of a public space (Rivlin 2007: 44) on the margins of private space. This interplay increases the likelihood of fleeting, spontaneous or chance encounters occurring (Hamilton 2002: 103; Rivlin 2007: 39; Stevens 2007: 73) with others who may be different from oneself. Street libraries do so by encouraging informal, inclusive behavioural rules and standards (Franck & Stevens 2007: 5) as a governing mechanism for low-stakes public socialising (Franck & Stevens 2007: 15, 19; Wolfe 2016: 34).

Thus it’s possible to see street libraries as an essential form of ‘social infrastructure’ for the way that they make a diverse range of social encounters possible by fostering, nurturing and amplifying community bonds (Chen 2022: 38; Latham & Layton 2019: 3).

Exploring the locality

Street libraries' significant drawing power (Rivlin 2007: 44) prompt community members to explore of unknown areas of their neighbourhood that they would not otherwise have reason or desire to visit.

- Density of street libraries means individuals can visit multiple street libraries in a single trip, reflected in Medowie’s dispersal of street libraries throughout low-density suburban streets.

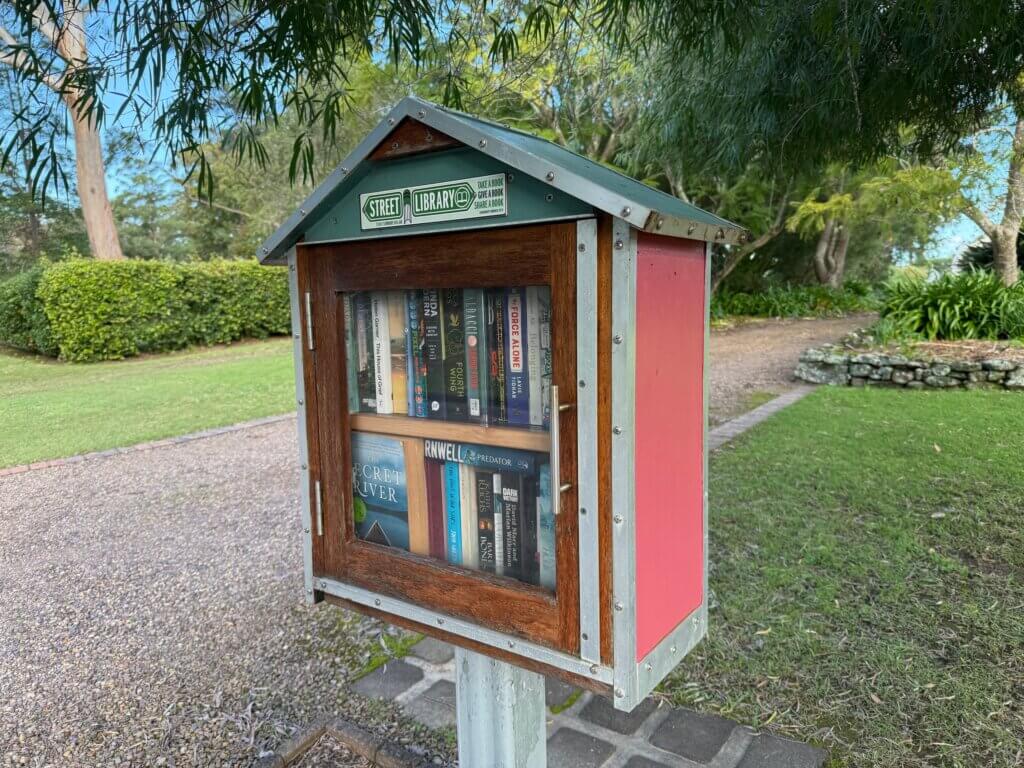

- Individuals exploring areas of the suburb they are unfamiliar with may engage with new sights, smells, noises, people and objects. This is seen in Medowie’s Lions Park street library (Figures 2 & 3), which encourages individuals who might not usually visit the park to do so, and for park visitors who would like to take a book to do so, and for both groups to also explore the park's natural surroundings and amenities (Figures 4 & 5).

Community involvement in the design: Individuals might be asked to contribute to the design through stickers (Figure 10).

Repurposed furniture: Street librarians have been known to repurpose TV cabinets, lockers, shelves, commercial refrigerators or other unused pieces of furniture (Figures 11, 12 & 13).

May 2025.

May 2025.

Figure 13. Street library, Medowie, May 2025.

Despite all aspects of the design being incredibly unique to each street library, street library designs in Medowie were found to exhibit three common characteristics, in that they all:

- provided an adequate (weather-proof and sturdy) place for books

- increased engagement with the natural and built environment, and

- act as a focal point for passers-by, with drawing power for repeat visits.

Promotion of a circular gift economy

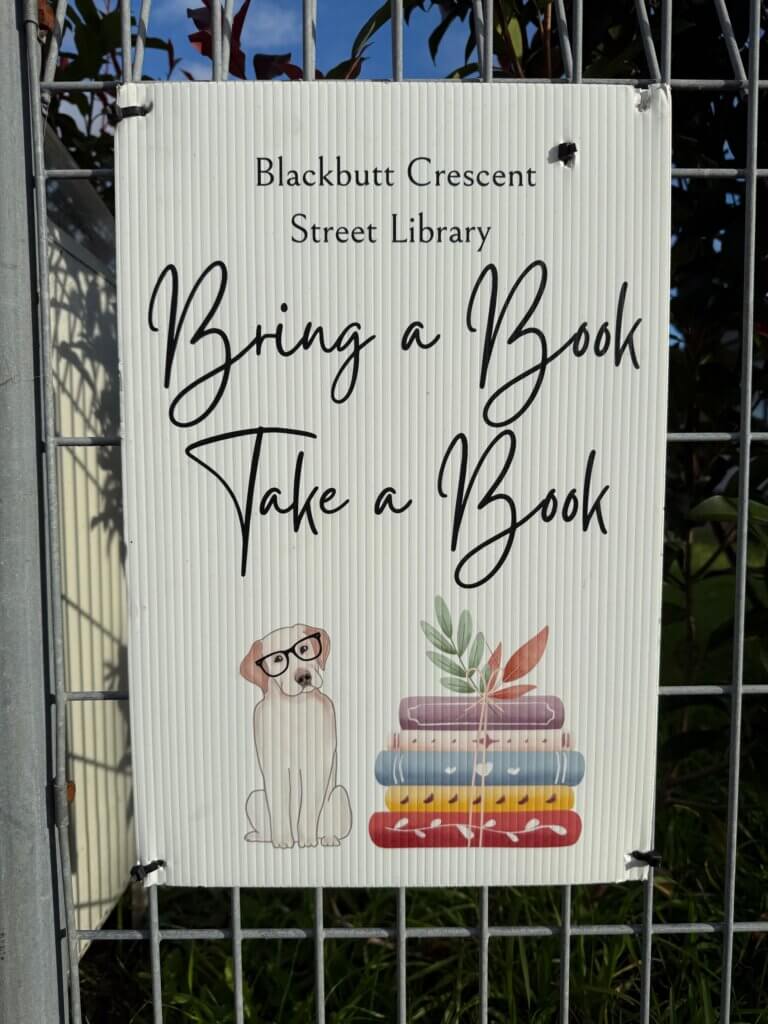

The famous German sociologist Georg Simmel once claimed that money ‘hollows out the core of things’ (Boy 2021: 195; Simmel in Hamilton 2002: 126), whereby a money economy creates relationships that are fundamentally transactional. Street libraries bypass the operation of money and transactional relationships by promoting a circular gift economy (Chen 2022: 27), exemplified in street library slogans and signs (Figures 14, 15 & 16).

Street libraries therefore contribute the following benefits to the local communities in which they are placed:

- Socio-economic benefits: they promote inclusivity and accessibility by removing financial barriers as a limitation to participation in reading

- Environmental benefits: they increase circulation of used books, which reduces the number of new books purchased and diverts second-hand books from landfill

- Social benefits: they facilitate largely anonymous, reciprocal exchanges between local residents (Chen 2022: 42), by increasing individuals’ social responsibility and ties to others through the expectation of giving, as well as taking, books.

Challenges to the success of street libraries

Street libraries situated too close to private space can become or feel highly monitored, forcing individuals to self-discipline and monitor their behaviours to ensure it aligns with the expectations of the space (Foucault 2008: 10; Rosen 2017: 328), creating highly performative interactions (Goffman 1971: 26; Hamilton 2002: 111). This can be due to:

- Proximity & positioning: The closer the street library is to the home the more physical and symbolic barriers (Foucault 2008: 3-4) are potentially created. If individuals must cross a public/private threshold to access the library, it may catalyse feelings of infringement on others’ spaces (Figures 17-18).

Figure 18. Street library, Medowie, May 2025.

- Excessively directional expectations: Displayed and enforced semi-formal rules may further contribute to a sense of surveillance (Foucault 2008: 4; Rosen 2017: 328) that discourage users.

When the activity of street libraries becomes regular, anticipated and highly controlled in this way through uses and expectations (Franck & Stevens 2007: 16-17; Rivlin 2007: 39), the social infrastructure of the street library may ‘tighten’ to the point that it is no longer part of public space. This means street libraries may decrease in attractiveness or inclusiveness to community members, thereby potentially reducing sociality (Peet 2018: 11; Latham & Layton 2019: 3; Thorpe 2022: 187). Street libraries therefore need to feel like 'unregulated' and 'loose' spaces for users to feel that they can linger, browse and engage.

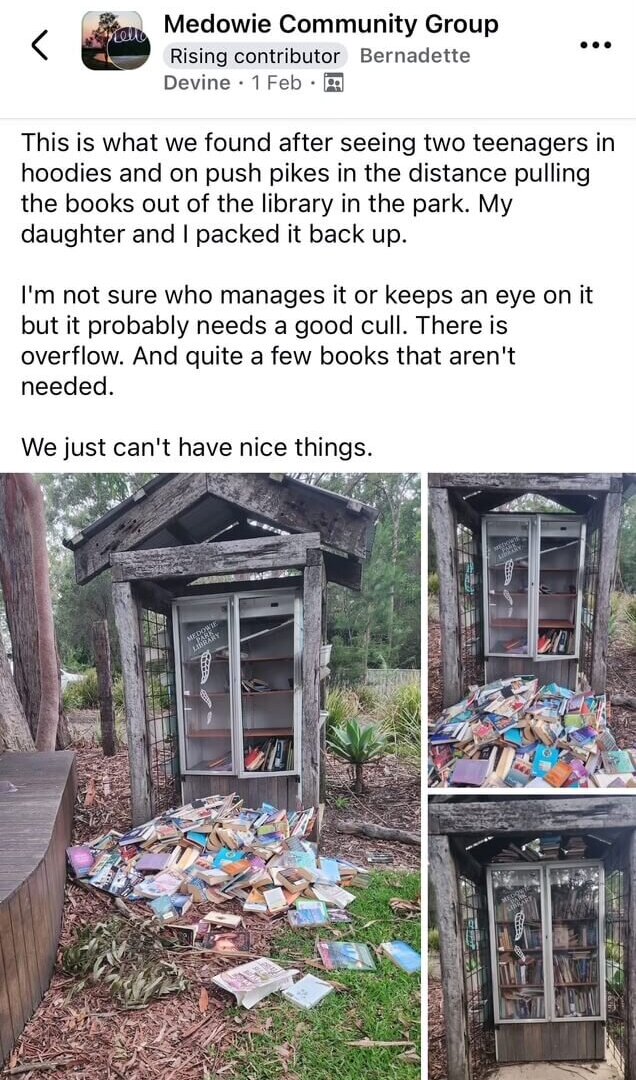

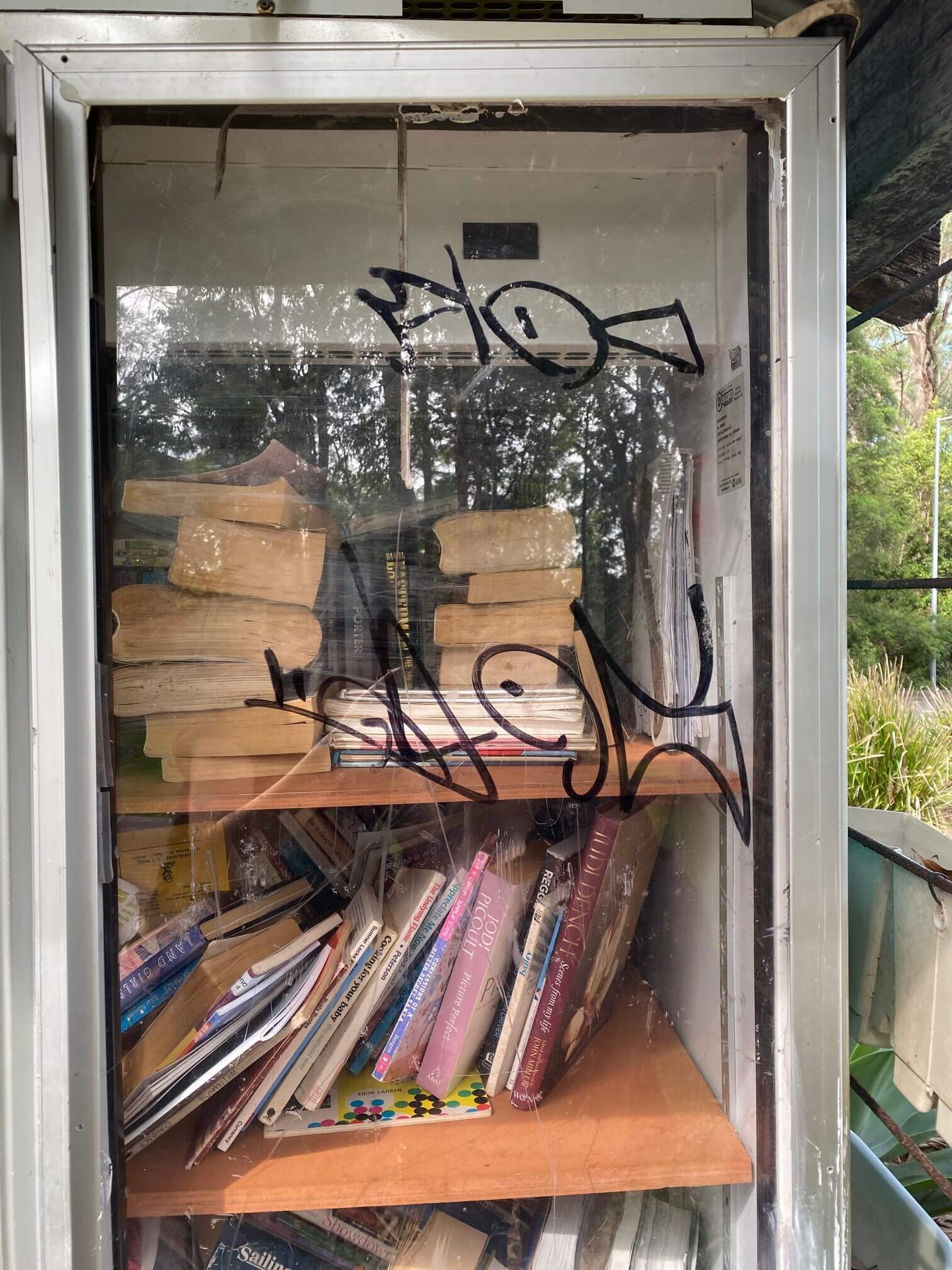

Conversely, public street libraries can feel too unregulated, if they are unmonitored and unsupervised, leading to an unclear division and allocation of roles and responsibilities. In this case, street libraries can become a form of social infrastructure that reduces community bonds and sociality (Peet 2018: 11; Latham & Layton 2019: 3).This reduction of bonds leads to individuals not taking responsibility for maintenance and upkeep of the street library, or even actively damaging or disrupting the street library itself. This can also be due to the context of a street library:

- Proximity & positioning: The further away the street library is from private, domestic space, an absence of care may be signalled. Individuals may then feel that ‘no-one cares’ for the public space and the street library. The consequences of this can be seen in Medowie’s Lions Park street library after it had its books pulled out and dumped and its glass door graffitied (Figures 19 & 20).

Source: Facebook.

Conclusion

This tour of street libraries in Medowie exemplifies how small, community-driven initiatives can transform everyday public spaces into street-level networks of reciprocity. By supporting a circular gift economy, fostering spontaneous social encounters, encouraging exploration, and promoting inclusive access to reading, street librarians, the libraries themselves, and their users care for both the physical and social fabric of the suburb. While challenges of over- and under-regulation remain, the enduring appeal of street libraries lies in their ability to be both familiar and surprising at the same time. Ultimately, they remind us that public space thrives when it is shaped by everyday acts of generosity, imagination, and connection.

About the author: Gemma Lavings is in her final year of her Bachelor of Arts, majoring in Sociology and minoring in Philosophy. Having lived in regional and urban areas, including Sydney, the Blue Mountains, the Central Coast and now Port Stephens, she has always been interested in the way design of public natural and built spaces influences how individuals navigate and engage in these spaces. She enjoys reading, writing and bushwalking—but most importantly, spending time with her two dogs.

*All images courtesy Gemma Lavings except where indicated.

Boy, J 2021, “The metropolis and the life of spirit’ by Georg Simmel: A new translation’, Journal of Classical Sociology, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 188-202, DOI: 10.1177/1468795X20980638.

Chen, PJ 2022, ‘The Contribution of Street Libraries in Australia to Literacy, Community and the Gift Economy’, Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 27-49, DOI: 10.1080/24750158.2022.2028332.

Fernando, NA 2007, ‘Open-Ended Space: Urban streets in different cultural contexts’, in KA Franck & Q Stevens (eds.), Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life, Routledge, London.

Foucault, M 2008, “Panopticism’ from ‘Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison”, Indiana University Press, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1-12.

Franck, KA & Stevens, Q 2007, ‘Tying Down Loose Space’, in KA Franck & Q Stevens (eds.), Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life, Routledge, London.

Goffman, E 1971, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Pelican Books, Victoria, Australia.

Hamilton, P 2002, ‘Chapter 3: The street and everyday life’, in T Bennett & D Watson (eds.), Understanding Everyday Life, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

Latham, A & Layton, J 2019, ‘Social infrastructure and the public life of cities: Studying urban sociality and public spaces’, Geography Compass, vol. 13, pp. 1-15.

Peet, L 2018, ‘Eric Klinenberg: Libraries and Social Infrastructure’, Library Journal, October 3, pp. 10-11, viewed 22 May 2025.

Rivlin, L.G 2007, ‘Found Spaces: Freedom of choice in public life’, in KA Franck & Q Stevens (eds.), Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life, Routledge, London.

Rosen, M 2018, ‘Accidental communities: Chance operations in urban life and field research’, Ethnography, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 312-335, DOI: 10.1177/1466138117727553.

Stevens, Q 2007, ‘Betwixt and Between: Building thresholds, liminality and public space’, in KA Franck & Q Stevens (eds.), Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life, Routledge, London.

Thorpe, A 2022, ‘Prefigurative Infrastructure: Mobility, Citizenship, and the Agency of Objects’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 47, no. 2, DOI: 10.1111/1468-2427.13141.

Wolfe, CR 2016, Seeing the Better City: How to Explore, Observe and Improve Urban Space, Island Press, Washington, DC