On public space: an interview with visual artist and curator Heidi Axelsen

Heidi Axelsen is a visual artist and curator working in public space through research-driven and social practice. She is passionate about creating meaningful places and experiences in public spaces and fostering opportunities for engagement with those who usually sit on the outside of city-making decisions. Her current focus is on public participation in the creation of regenerative public artworks and public domains.

Heidi trained in Sculpture at the National Art School and is director of MAPA Art + Architecture with architect Hugo Moline. MAPA is an art and architecture collaborative working between the social and the spatial. MAPA have created public artworks and exhibitions commissioned by Westmead Hospital, City of Sydney, Echigo Tsumari Art Triennale, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Forbes Hospital, MAMA gallery, Defence Housing and others.

Alongside her creative practice she has worked in local government in Cultural Development at Fairfield City Council, in Creative Industries at Blue Mountains City Council, assistant curator at Bankstown Art Centre, public art consultant at Parramatta City Council. Heidi is currently doing a Phd by practice at Monash ‘reframing public art as a form of living maintenance’.

As an artist, what draws you to working in public spaces, and how would you define them?

I love the unexpected things and encounters that happen in public spaces. It’s where people of all types can converge, where the power dynamics of land politics and discordant values collide. Moments of resistance and celebration are all on display. It is where a conversation you didn’t know you were going to have might happen. You might feel connected, challenged, surprised, unsafe, delighted or bored.

A public space says so much about the people around it and the lives they live. Is it a well-cared and well-worn space? A sterile and highly controlled empty place? A dirty well-used chaotic space? A place people have made themselves? A place allowed to be taken over by plants?

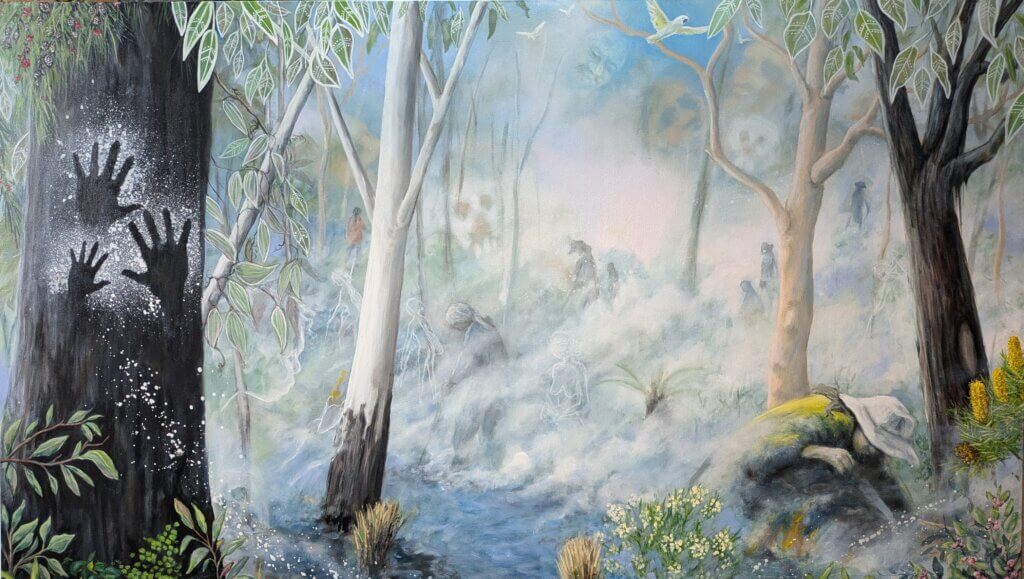

A great public space, I think, is defined by its diversity and softness. A great public space makes room for Country to return and can hold a diversity of people, activities, plants, animals and is surrounded by diverse housing types.

Does it matter if you have money or not? Do you feel joy there? Can you wear whatever you want? Do you want to play or relax there? Does it fill you with a sense of possibility or is everything prescribed? I also think a great public space makes space and opportunity for people to contribute to place themselves.

How has your own experience of place influenced your professional practice?

My experience of making home again and again in new places as both a child and an adult, has greatly influenced how I approach working as a professional in public space. I feel so grateful that I’ve had the opportunity to make strong connections with so many beautiful and nature rich places on this stolen land. I have become highly attuned to what is getting displaced by the processes of redevelopment and to what power dynamics are at play. What brings respite and what brings connection, and inversely what creates exclusivity, what stops you dwelling and makes you hurry on? I am always asking what could be maintained and nurtured. More importantly than what needs renewing, I think it is important to ask what could be left alone or supported?

You describe your work as relational, collaborative, and durational. How do these principles shape the way you approach public art and spatial consultancy?

These words describe a way of working; one that is dependent on building relationships and that doesn’t preference any one individual voice over collective voices. This way of working takes time. As much as the physical and environmental characteristics of a place matter, so does the process of how you work in a place. It takes time to understand the context, to build relationships, to learn what is already working and what already exists. In making public art and public spaces, the normative process is to have a vision of a finished state and work towards that. The end-result and quality of the space/object matters of course, but it’s definitely not the end goal. Nothing is static or finished so I’m interested in making work which is a tool, an experience, a platform or beautiful thing for continuous and evolving connections to place.

What does “provoking alternative possibilities” mean in practice? Can you share an example where this led to a transformative outcome?

In practice this means always asking the question...is there another way we could do things? Do we let normative ways of city making to define what we do and how we do it? Or is there others way of relating to our world and each other? Who can we learn from? For example in the world of public art within private development, it is typically an afterthought or a box ticking exercise to aid in the planning process of new development. The Open Field Agency project was designed to provoke other possibilities within this constrained and problematic model of commissioning public art. Centred around Dank Street South Precinct in Waterloo, the Open Field Agency project is an artist, architect and community led experiment in delivering public art over time within private development through durational residencies. It is public art reframed as a slow, incremental process of making private development more public.

What if some of the power that developers and city authorities hold to shape future public spaces was really shared with the communities who already live there?

Getting started on the project we asked... Who are the traditional custodians of this place? What future do they want? What if local people had a genuine way to shape future developments? What if local people, with the aid of artists, landscape architects and architects, made their own masterplans? What if some of the power that developers and city authorities hold to shape future public spaces was really shared with the communities who already live there? What if we turned the public art commissioning model on its head and artists and communities started work before any developers and diggers did? What if artwork was a structure and program to allow artists and community to work in this place before, during and beyond development? Could the artwork do something to support those practices which are getting pushed out by redevelopment?

The Open Field Agency Residency infrastructure, the Field Rooms completed in September 2025, is now hosting artists, scientists, architects, carers, historians, performers, researchers, students and others in a residency space. The task of Open Field Agents is to tend to the openness of this place, its social and spatial openness through their own work, research, conversations and creations. As artist/curator I am excited to be working with the selected residents to see what we can do here.

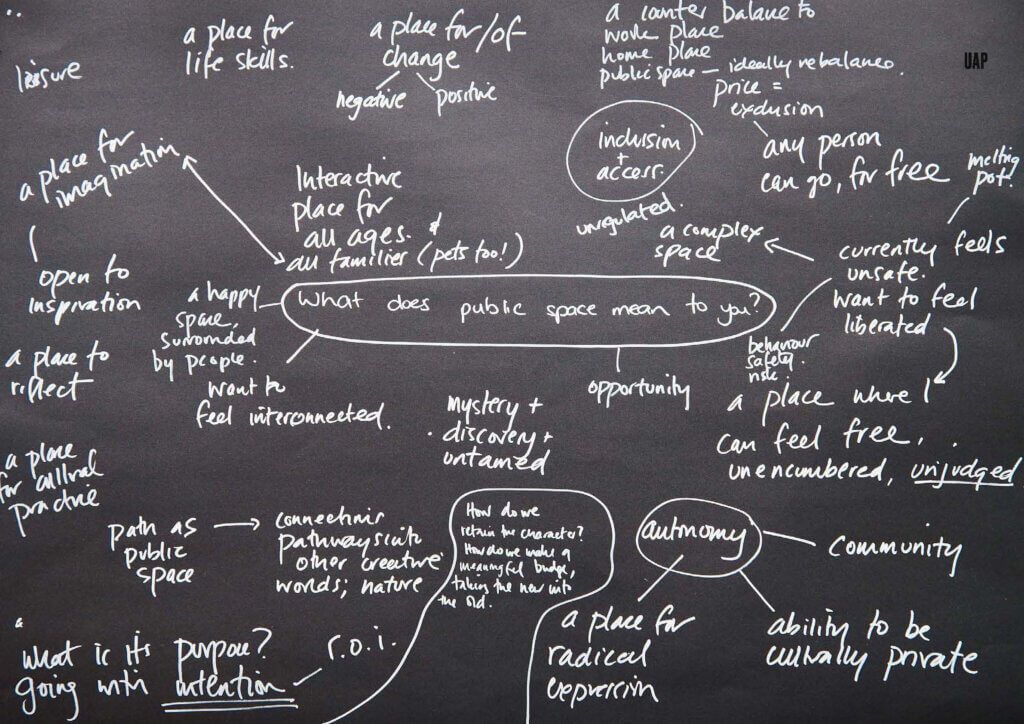

Co-design is central to your process. How would you explain what co-design is, and how do you ensure diverse voices can genuinely influence the design of public spaces? What challenges have you encountered in co-design workshops, and how do you navigate power dynamics between stakeholders?

Often the challenges are not so much in the workshops themselves, but are in the broader systemic processes of city making. It is a challenge is to convince commissioners to realise the value of co-design processes and to invest in them. There is a perception that participation and co-design will slow things down, make it complicated. In my view that’s great, if it is slow it means you are doing co-design genuinely. We need a whole lot more thoughtful development and less development in general. It is also a real challenge to ensure that co-design and participatory processes aren’t tokenistic and extractive. People’s contribution and time must be valued, recognised, paid and where possible translated into real outcomes.

There is no single mode of co-design which works; different methods and different approaches might work depending on the context. For some people, speaking in a group context is not safe or productive, or some may be suffering consultation fatigue. We often use non-conventional ways of co-designing, for example, holding hour long free-ranging conversations with 64 individuals over coffee and cake, or creating a newspaper dispensing box that local people can contribute to themselves, or creating a film together, or simply sharing a meal. Sometimes we make things, objects, props first up and then that starts conversations.

Although we advocate for it there isn’t always the time, budget or space to allow for co-design processes. When making work for galleries or festivals we also make speculative and propositional work.

Your projects involve architects, planners, engineers, and local governments. How do you balance artistic vision with technical and regulatory constraints?

With great patience and trying to enjoy constraints as they can be wonderful things to wrestle with and produce more creativity.

What have you learned from working with such a wide range of collaborators?

I’ve learnt that people some people want to follow business as usual processes and some are up for trying something new. An open collaborative spirit can go a long way, and being clear, is being kind.

How do you uncover the stories and histories of a place during your research? Can you share a project where place-based insights significantly changed the design approach?

I do a deep dive into the story of the place I am working within. This might mean archival research, talking with local people, visiting historical societies, community reference groups, or chatting with people who are hanging out on the street. So much is learnt from simply spending time in a place and talking with people.

I am fascinated by the many uses of a place over time, the things that happened there, things people did or made there, and equally I’m interested in what people would do in a place if they had the chance to. What is getting displaced by development and who is getting designed out is always at the front of my mind. We often create props or devices in public spaces, not as an end in themselves but to offer an invitation to connect with people and learn about a place.

What we learnt about our time in Waterloo, was that people really valued a space to come together, to exchange, to share without having to spend money. People wanted a place they could contribute to and feel some ownership of. There is a great absence of these kind of spaces in Sydney. So the artwork we made is part cultural infrastructure, part prop, part creative workspace, part program, in part an object symbolic of the precarity of creative practice itself.

In your experience, what role does art play in shaping the identity and future of a place? How do you see public art contributing to social capital and community resilience?

Mierle Laderman Ukeles (one of my favourite artists) made a work called Social Mirror in 1983, a garbage truck faced with mirror reminding people of their role in producing waste and highlighting the value of service and maintenance work. I love this work for many reasons and it literally reminds of me of the possibility of art as a mirror to reflect both the ugly and beautiful things about our culture. Ultimately art can show us ways in which we might transform our relationship to the world around us. I don’t think it is so linear that art shapes place…but rather its does a complex dance …Country and people shape art and art shapes Country and people, and hopefully it goes on and on like that.

Does public art help shape the identity and future of a place? Does public art contribute to social capital and community resilience? For the converted, such as myself of course inherently I know art plays a powerful role here, but it’s tough to measure and prove it. It also depends on what you call public art? Is a sculpture in the foyer of a private building public art? I would say it is art which a select few can enjoy, but some people are happy to call that public art. As professionals working in public space we need to advocate for public money (even when coming from the private sector) goes towards making open, inclusive and accessible public space and public art.

Making art is one of the most precarious occupations around and needs scaffolding to survive. Artists on average only draw in 38.5k per annum from creative practice and arts related income combined [1]. I think it is quite a simple recipe. When all types of people and especially artists can afford to live in a place and are given the opportunity to contribute and care for it, it will be an amazing public space.

[1] Artists as Workers: An Economic Study of Professional Artists in Australia by David Throsby and Katya Petetskaya, 2024.